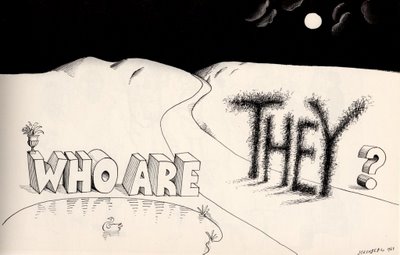

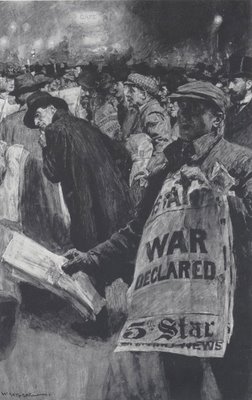

Paging through Victorian era magazines you will find thousands of dull, unimaginative illustrations that long ago ceased to have relevance to anyone. But every once in a while you find an illustration that leaps off the page, grabs you by the lapels and shakes you. The rare artist with "the spark" still stands out.

Most of his peers have been blissfully forgotten, but English illustrator William Hatherell (1855-1928) had "the spark" and deserves to be remembered for it.

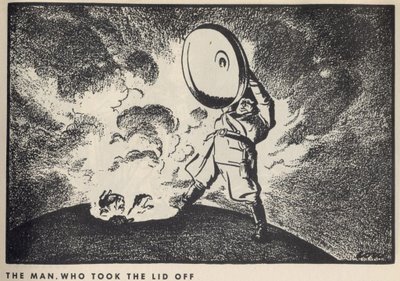

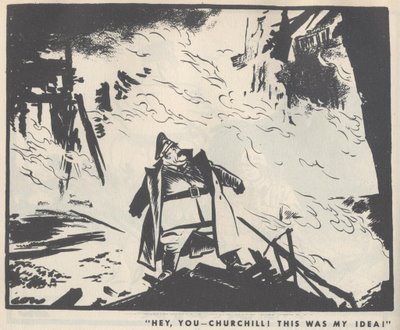

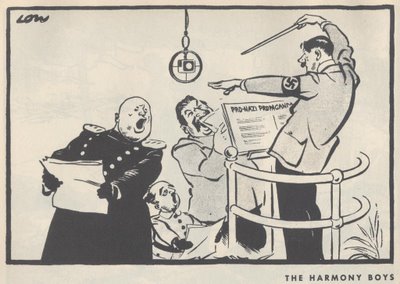

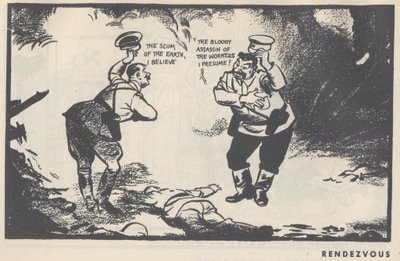

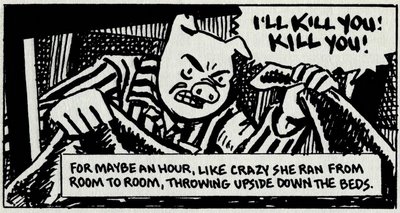

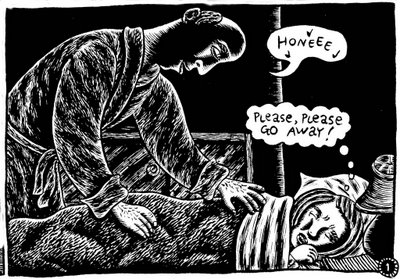

This drawing overcomes every disadvantage that the world could throw in its way: working in black and white with charcoal and wash, reproduced in a publication with poor printing quality in a period when the prevailing style was largely fusty and stolid, Hatherell produced a picture of striking strength and vitality measured by the most modern standards.

His composition has all the verve and excitement of an illustration from America in the 1960s. His potent use of values, his vigorous strokes and the careful placement of figures result in a picture more dynamic and lively than much of what is produced today using the latest computer graphic technology. It just goes to show you that even if you are born in the wrong place and time, working with the wrong tools, sheer talent can do a lot to level the playing field.

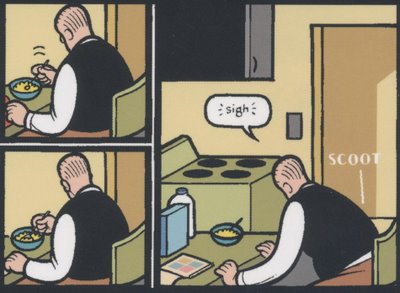

I don't have access to the original of this drawing by Hatherell, but I am attaching below some details from another one of his drawings so you can see his technique.

Hatherell worked on the staff of a magazine called The Graphic starting in the early 1890s.

In less capable hands, this drawing would lapse into a nondescript puddle of gray. Only Hatherell's mastery of value maintains the integrity of the picture.

You won't find much of his work around these days, but this was a man who could draw.