In Gerardo Naumann's "Factory" performance during the Warsaw edition of the inspiring Ciudades Paralelas festival - we are taken on a guided tour of a functioning factory (in Warsaw it was an enormous steel factory). However, this is not your average tour. Here, we get the possibility of witnessing private stories of workers, to hear who they are, both within the company context and outside of it. The tour is at times poetic, at times simply human and direct. Every presentation mixes the description of a person's job with more personal matters. Our first guide is the factory's technical director, then we go all the way down the (wage) hierarchy to the gardiner, who also has his stories, telling us of his love for 60's music (Deep Purple et al.) and even making us listen to some of it. A truly human experience in an unexpected context.

So what is it that makes me uncomfortable about it?

It is an unwilling, yet uncritical, PR event for a huge, powerful and hardly uncontroversial business.

The project seems to follow closely the teachings of French philosopher Jacques Rancière - for several years now he has been advocating a change of paradigm in the way we look at others. Teaching something, or learning, should mean, above all, realizing how the way other people see the world is just as valid as ours - it is a structure that is already a "complete" structure, they are also "teachers" and we - students. To put it in other words - everyone is competent. It might just be a question of acquiring the possibility to further develop this competence.

Rancière gives this example: workers in a factory can also be seen as art aficcionados, as they have their (art, or aesthetic) specialities, their passions, their expertise. Tapping into this is, according to Rancière, a crucial step towards going beyond the simplistic emancipatory claim of passing on the "correct" sensibility.

The "Factory" project follows Rancière's ideas closely. And yet, all the while achieving an arguably closer relation with the subjects/performers, and while making us feel a bond with many of them, while amazing us with the aesthetic aspects of a factory, its dynamics and dramaturgy, it fails in an important aspect: it underestimates the power of the structure it works in.

"Just" showing the lives of the workers is never just showing their lives. It necessarily functions within the context. And this context, here, wins. The tour/performance becomes a scarily effective way of implementing propaganda. We are still given stories about how magnificent it is to work here, how everyone is happy, safe, friendly, how everyone who worked in the factory during communist times participated in strikes, and how the only mentioned case of someone getting fired... got immediately offered another job. And because a skillful theater director does it, we hardly feel manipulated. On the contrary, the "genuine" feeling prevails. We leave happy that things are as they are. We love the stories, the people, the parallel city, the way it works, the world it works in. It is difficult to imagine a better publicity.

But wait - could all this be true? Maybe it is a good company? Maybe it is happy and safe and the best of possible industry worlds? Well, it's enough to make a quick news check - there was a fire in the factory just a few months ago, and just recently the company just layed off many of their executive personnel (apparently they were transferred to another company for "effectivity reasons" and were subsequently fired). I dig a little deeper. ArcelorMittal - that is the name of the company, is owned by the 6th richest person in the world (with a personal wealth of $38.1 billion - link). The company made 10 billion dollars profit last year alone. On the other hand, since the company started taking over Polish factories, it diminished its staff by some 3000 workers in Poland (ca. 25%).

This type of criticism could be contested. Should this matter? Should the work of art take this into account?

Can it? How?

Can we play with the system, within the system? Can we work our works so as not to become victims of the same propaganda we would usually receive - or worse, not just victims, but advocates?

Or can we ignore this and consider that not all works of art need to be political, or not necessarily in that sense, that it can also be about the people who work there, that they too have the right to be important subjects, and not just the megarich owner of their company?

But if we just move in and focus on them, while remaining on the factory ground, if we call it a Parallel City (Ciudades Paralelas means Parallel Cities), aren't we playing the status quo game? Aren't we the perfect PR people, giving the company - and the world which it co-creates - our seal of approval, a "positivist" acceptance? (A disturbing trait of the performance is that the workers/performers come and go - without too much of an introduction, and with no goodbye whatsoever, so while we are kept entertained, they have nearly no chance of receiving our recognition, or of establishing a human contact beyond the script. The beginning and the end is clear - it is the Ciudade Parallela, the company, not the people). Doesn't the critical art, so cherished by Rancière, become uncritical because of the very same (human) aproach he proposes?

So how are we to make - and look at - art in all those parallel cities that are more and more often taken over, or at least manipulated by, the powers that be, be they economic, or more directly political?

The fight here is indeed a fight over the sharing of the sensible - how do we value what we see? How can we reevaluate it? What sort of sharing is this? What do we want out of this situation? How can we, as artists, but also as viewers (viewers are artists, but artists are viewers too, to many people's surprize), find a common ground without becoming the agent of some powerful megastructure? Should we worry about it?

Banning the word "Facebook" on TV might seem like a silly idea, but I know some theater companies who do not use any brands in their shows. And for them, it's not about having the power to change the world. It's about enjoying the possibility.

----

Curiously enough, I was told that when Naumann made an analogous performance in Buenos Aires, the factory was a small and badly run one, and some commentators thought he was too rough on it, making it look very bad. One possible answer is: this format simply gives you the possibility to take a peek inside - and whatever you find there has been there already. But another possible explanation is: it may not be enough to implement a "personal guided tour" formula if we want to move beyond the small industry into the big guys' terrain, where they know how to charm us, seduce us, and make it appear like it's all immaculate. Then, it seems, it would need to be a whole new ball game.

---

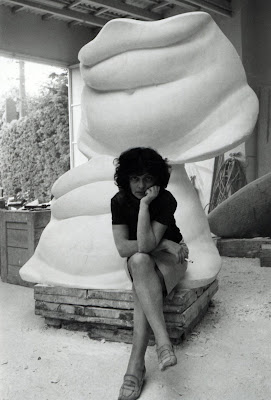

I have a vague recollection of reading about a performance by the great Brazilian visual artist and performer Hélio Oiticica (I couldn't find the reference now). I believe it took place in the 70's. Oiticica walked around the public space, pointing at different objects. The spectators which followed him understood (were told?) that through the gesture, the objects acquired the status of works of art.

Oiticica's enchantment with the world seems clear. This is what the world is like, he seems to be saying. Look at this piece of art! I couldn't have done this better. The only thing I can do is to point it to you.

What would happen if Oiticica did the same thing in the factory? Would the objects he pointed at stop becoming art? Certainly not. The factory would gain the status of an aesthetic object - it would become the same marvel as any of the trees, benches, stones, clouds. Look at this piece of art! I couldn't have done this better.

Could we not?