Young Norman Rockwell dreamed of the day he would paint as well as his idol, the great illustrator J.C. Leyendecker. Rockwell spied on Leyendecker, trying to discover the secret of his genius:

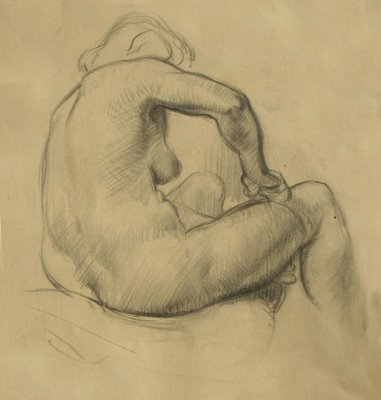

I'd followed him around town just to see how he acted....I'd ask the models what Mr. Leyendecker did when he was painting. Did he stand up or sit down? Did he talk to the models? What kind of brushes did he use? Did he use Winsor & Newton paints?But Leyendecker's secret had nothing to do with his brand of brushes. A few years later, Rockwell visited Leyendecker in his studio and observed Leyendecker working on the painting above. He recalled:

New Rochelle published a brochure illustrated with reproductions of paintings by all the famous artists who lived in the town. Joe worked on his painting for months and months, starting it over five or six times. I thought he'd never finish it.The painting was beautiful, with many fine touches.

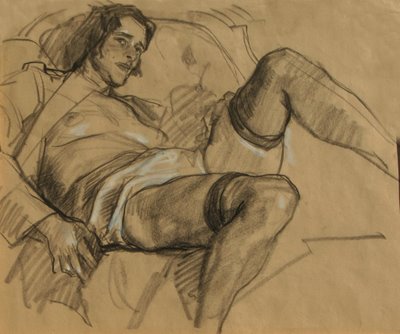

It was nearly finished, and the client would have been happy to get it. Yet, Leyendecker remained unsatisfied. Rather than completing the painting, he set this version aside and started all over again, searching restlessly for the image he wanted. The final published version looked like this:

Nietzsche once wrote, "you admire the beauty of my spark, but you don't feel the cruelty of the hammer on the anvil that makes it happen."

Leyendecker paid a heavy price for that spark. Whatever it cost, the young Rockwell must have concluded that it was worth it. When Rockwell's turn came, he paid too. Rockwell may not have traded his soul to the devil, but he painted "100%" in gold at the top of his easel to make sure that he never gave anything less. That credo kept Rockwell at his easel seven days a week painting countless studies and refining his craft as his first wife filed for divorce and was hospitalized for depression. She was alleged to have committed suicide. His second wife was hospitalized for alcoholism and depression. Rockwell himself sought professional help for his own depression. And yet, the brilliant pictures kept on coming.

Today, we admire such artists from a safe distance. Few of today's heavily promoted artists are willing to spend the same time on the anvil. I can't say that I blame them, especially when most of their audience is incapable of distinguishing real sparks from glitter.