The sad thing is that more and more, we are becoming disconnected with a sense of wonder, of mystery and destiny.

Joel-Peter Witkin

It isn't hard to think up something very deep and poetic concerning Witkin:

through his imagery, we gain a greater understanding about human difference and tolerance, someone

declares.

Someone else seems to admire Witkin for nearly the opposite:

His arresting images show us our powerlessness in the face of madness, lust, disease and death.

The thing about Joel-Peter Witkin is that he

shows people. And daringly so. The strangest people you have ever seen. In the strangest of poses. In the most surprizing situations. And, although his pictures are full (some say: overfilled) with references to art history, his merit seems to be above all related to this:

showing.

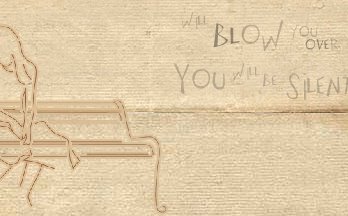

How does he find his models? Some of them in the morgues, others, from ads. Ads like this one from 1989, looking for:

Pinheads, dwarfs, giants, hunchbacks, pre-op transsexuals, bearded women, people with tails, horns, wings, reversed hands or feet, anyone born without arms, legs, eyes, breast, genitals, ears, nose, lips. All people with unusually large genitals. All manner of extreme visual perversion. Hermaphrodites and teratoids (alive and dead). Anyone bearing the wounds of Christ.(...) Anyone claiming to be God. God.

Someone states that seeing Witkin's works is like witnessing a brutal car crash. Indeed, we feel voyeuristic, as in, willing to witness obscenity. Being the good art amateurs we are, we look for justifications, just as we might look at the crash "from a distance", inquiring into the reactions of others, or the aesthetic vs. ethical aspects of the scene. We might even go so far as to declare the paintings a cry for tolerance. The question remains: how distant is this cry from the freak-shows history has known time and again? Isn't it just the curiosity of the crippled, the strange, the too-different? Seeing the world without its regular masks?

And if we are just part of a long line of curious onlookers, are we damned? As in, morally condemnable?

The concept of

monster, which made a career during the Renaissance,

comes from the Latin verb

monere, to warn, and/or from the Greek root

teras,

meaning something both horrible and wonedrful.

Contrary to common belief,

monsters weren't only associated with signs of evil events to come, but also, and quite frequently, with signs of devine power. The

monster shows were often events where one would discover the many ways of divine creation. (Notice how words like "amazing" and "awesome" also have an ambiguous quality at their origin, but went the other way, becoming generally accepted as positive adjectives).

In this sense, what we see, through Joel-Peter Witkin's eyes, are monsters. They are the marvels.

They are the graces of a wonder-ful world.

Should we believe that Witkin is genuinely preoccupied with the people he photographs? Yes, there seems to be no doubt about it. He is deeply religious, but has found a home in the esoteric side of religion. And with it comes the love for the

awesome, the

excentric. And a fascination for, or empathy with, the humans within this underworld. He is interested in their stories, and openly

declares that his art is "not intended to reveal what the individual subject chooses to hide but instead to make the hidden qualities more meaningful."

Meaningful they become. But

what is their meaning? And does it not risk turning against those he claims to defend?

One of Witkin's many critics,

Cintra Wilson, writes,

The work is beautiful enough to be "real art," but it is still an intellectually camouflaged, carny peep show of the most debased and obvious water. You can put as many flowery wreaths and as much gorgeous photo technique as you want around a dead baby, and it will be art, yes, but it is still a dead baby. It is still a sideshow for the morbidly curious, regardless of how much Witkin may drone on about the deeply religious quality of his work.

(...) The artists I respect get more irreverent with age while, at the same time, they humanize; they lighten up, they drop the old mask, they actually start to care about things more and open up a little, laughing about things they used to take to heart as deathly serious. They evolve -- for better or worse.

Then again -

Francis Bacon, in that sense, did not evolve, did he?

(the first image is the portrait of Witkin by his wife, tattoo artist Cynthia Witkin)Also check out one of the most recent of Witkin's albums: