CNN reports:

Mo Xiaoxin, a 56-year-old assistant professor at a university in Changzhou, in eastern Jiangsu province, shocked students by stripping during a lecture on "body art" to emphasize the "power" of the body and to "challenge taboos," the Beijing News said.

"There are no taboos in the field of research, but to do this directly in the course of teaching is obviously not appropriate," the paper quoted Tian Junting, a culture ministry official, as saying.

The lecture was part of a course within a newly established "human body art and culture" research institute -- China's first -- at Jiangsu Teachers University of Technology, the paper said.

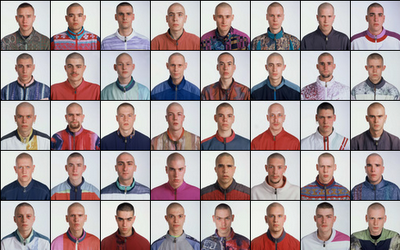

Mo arranged for four other models, including a man and woman in their 70s or 80s, and a younger couple, to strip naked in front of the class while he lectured, the paper said.

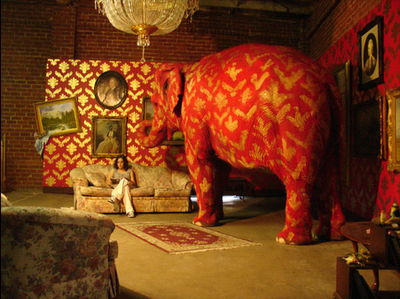

Scandal? Or trivial event? Are we to see this through the eyes of an art critic for whom a naked body is just another element of artistic expression? Or should we rather interpret it from the students' point of view? Would it then be an indecent act, a very embarrassing one? Of course, the article says little about the context of the class. It was part of an experimental course on body art. But was it a practical course? Is a practical course in body art actually possible? I've heard of body art workshops where people were encouraged to self-mutilate. How exactly does that work? Does one train various techniques, until one gets them right? Is there a set of "exercises" one has to execute to pass?

If we accept that a significant part of contemporary art looks to go "out of the box", teaching it becomes a challenge. Trust me, I know. The whole idea is how to get someone to accept the excentric as central, i.e., how to see ("alternative") contemporary art as a basis, or a context for work. This is extremely difficult, much more difficult than just learning to appreciate it. On one hand, the students need to comprehend the strength of new works, the impact they potentially have; on the other, it's not enough to see it in a distance, in an attitude of all-encompassing tolerance. This - body art, performance, controversial or plain shocking installations - is to be, if not a foundation, at least a contemporary history. That means, it needs to be close enough to be useful, to be felt as something we might have done, but (often fortunately) don't need to do any more.

Does this mean the teacher was right? Only if he achieved his goal. Only if the people watching him not only got the point (their point, not necessarily his point), but also, will feel empowered through the experience.

But teaching it? Or: actually doing body art (if getting naked comes anywhere near as much as an introduction to body art) in front of the students? Two points irritate me here:

1) A teacher that instead of making the students discover things by doing them does them himself is at least suspicious. I'd rather have a scandal where the teacher convinced students to actually do body art. At least then, they are the performers, and not just forced spectators. The article states that the teacher tried making the students undress too. It seems it didn't work. Was there any room left on the stage?

2) On a more personal level, art that aims to "break taboos" rarely ever speaks to me. It's not too hard to watch. It's too easy. As one ex-body artist said, the performers are not the only ones sweating. The audience sweats too - of a specific embarrassment and more often than not, a deep desire to be somewhere else.

My doubts regarding Mo Xiaoxin are both as a teacher and a perfomer. But they have little to do with indecence.